To know where we are going, it is important to understand history – An insight into the Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire

Summary

- On 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan launched a Turkish-backed military offensive to recapture Azerbaijani territory occupied by Armenia around Nagorno-Karabakh, which was costly but largely successful;

- On 9 November, the Armenian, Azerbaijani and Russian governments signed a ceasefire agreement effectively refreezing the conflict to the disadvantage of Armenia;

- Nagorno-Karabakh will remain controlled by its Armenian government and its road access to Armenia guaranteed, but Azerbaijan will recover all other territories otherwise;

- A peacekeeping contingent of some 2,000 Russian soldiers will oversee the ceasefire, effectively asserting its primacy in maintaining the new status quo, while accepting greater influence by its rival, Turkey;

- Political instability is very likely in Armenia in the short-term, but there are also risks for Azerbaijan in the medium- to long-term;

- Periodic skirmishes between Armenia and Azerbaijan outside of Nagorno-Karabakh are likely to persist, but the risks to energy infrastructure have fallen;

- A regional war between Russia and Turkey is unlikely due to the mutual lack of viable gains and the multitude of steps to apply pressure elsewhere;

- Turkey has provided a new battlefield concept that is likely to become increasingly widespread in armed conflicts elsewhere for as long as effective anti-drone capabilities do not exist.

Figure 1 – Source: www.polgeonow.com

CONTEXT

Nagorno-Karabakh is a remote mountainous region situated in south-eastern Azerbaijan, with a population of some 150,000 that is almost entirely comprised of ethnic Armenians. In 1917, in the wake of the collapse of the Russian Empire, ownership of the region was violently disputed by the newly independent Armenia and Azerbaijan, with the former succeeding in seizing territorial control. In 1922, when Armenia and Azerbaijan were integrated as Soviet Socialist Republics (‘SSRs’) into the USSR, territorial ownership of the Nagorno-Karabakh oblast was formally granted to Azerbaijan – although it was granted regional autonomy.

The national issue of Nagorno-Karabakh remained active during the Soviet era but gained pace from 1988, when popular pressure by the Armenian majority for union with Armenia prompted Azerbaijan to reorganise the region under its direct control amid increasing interethnic violence. In 1992, amid the dissolution of the USSR and the collapse of a Soviet-brokered compromise between Azerbaijan and Armenia, a full-scale war broke out between the two newly independent states. Azerbaijan received material support from Turkey and Israel, as well as Russia, which was also the main backer of Armenia. Hostilities continued until May 1994, when Russia mediated a ceasefire. By this point, some 20,000 military personnel and 2,000 civilians had been killed, and approximately one million people displaced.

Since the 1994 ceasefire, the situation around Nagorno-Karabakh has been a frozen conflict, occasionally punctuated by skirmishes between the Armenian and Azerbaijani militaries, which are positioned along a Line of Contact formed of trenches and fortifications. Nagorno-Karabakh, which had declared itself the Republic of Artsakh, remained in the orbit of Armenia. Meanwhile, the Armenian military had occupied seven districts outside of Nagorno-Karabakh, accounting for up to 9% of Azerbaijan’s territory. This remote woodland forms a geographical buffer between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, the only main supply route between which is the Lachin Corridor.

Hostilities are not only confined to Nagorno-Karabakh, with skirmishes having respectively occurred in 2012, 2014 and 2018 in the northern provinces of Tavush (Armenia) and Qazakh (Azerbaijan), as well as in Nakhchivan, an Azerbaijani autonomous exclave to the southwest of Armenia – one village of which is also occupied by Armenia for tactical purposes. In this sense, Nagorno-Karabakh is the flashpoint of a wider interstate standoff.

In order to avoid outright war with Azerbaijan, Armenia does not formally recognise the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh. Despite regular talks brokered by the OSCE Minsk Group, a peace treaty was never agreed. Since 1998, both parties have adopted maximalist stances on the issue, thereby crystallising public discourse around two worldviews that are mutually incompatible because they deny the cultural ethnicity of the other group. It is a touchstone in the domestic politics of both countries, with concessions threatening government stability. In particular, there is a powerful nationalist bloc in Armenia, two of whose presidents have been natives of Nagorno-Karabakh.

CURRENT SITUATION

In July 2020, renewed skirmishes between Azerbaijan and Armenia broke out. An exchange of drone and artillery strikes in the Tavush (Armenia) and Qazakh (Azerbaijan) regions resulted in the deaths of at least 17 military personnel, including an Azerbaijani major-general. This prompted opposition-led protests in Baku, which called for war. Through July and August, the Azerbaijani armed forces conducted military exercises with Turkish support.

This appears to have foreshadowed a major offensive by Azerbaijan, which was launched on 27 September. Supported by Turkish drones, military advisors and, allegedly, jihadist mercenaries from Syria, the Azerbaijani armed forces succeeded in capturing Armenian-controlled territory to the south of Nagorno-Karabakh along the Iranian border, as well as the city of Shusha, which overlooks Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital, Stepanakert. Baku and Ankara appear to have taken advantage of the distracted global environment, as well as the need to act before harsh winter weather set in.

Over the course of the fighting, both sides also targeted infrastructure outside of Nagorno-Karabakh in artillery and rocket attacks. For example, Azerbaijani units destroyed a bridge linking Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh, while the Armenian military shelled Azerbaijan’s second-largest city, Ganja, on four occasions, narrowly missing oil pipeline infrastructure.

As of 22 October, according to estimates cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, almost 5,000 people had been killed during the renewed hostilities, most of them in and around Nagorno-Karabakh. The toll has likely risen considerably since then.

Ultimately, the Armenian and Nagorno-Karabakh armed forces were overwhelmed by the military superiority of the Azerbaijanis and Turks, losing approximately 100 tanks, 50 armoured combat vehicles and 130 artillery pieces – or some 35% of its inventory. On 9 November, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev signed an agreement brokered by Russian President Putin, which established a full ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh.

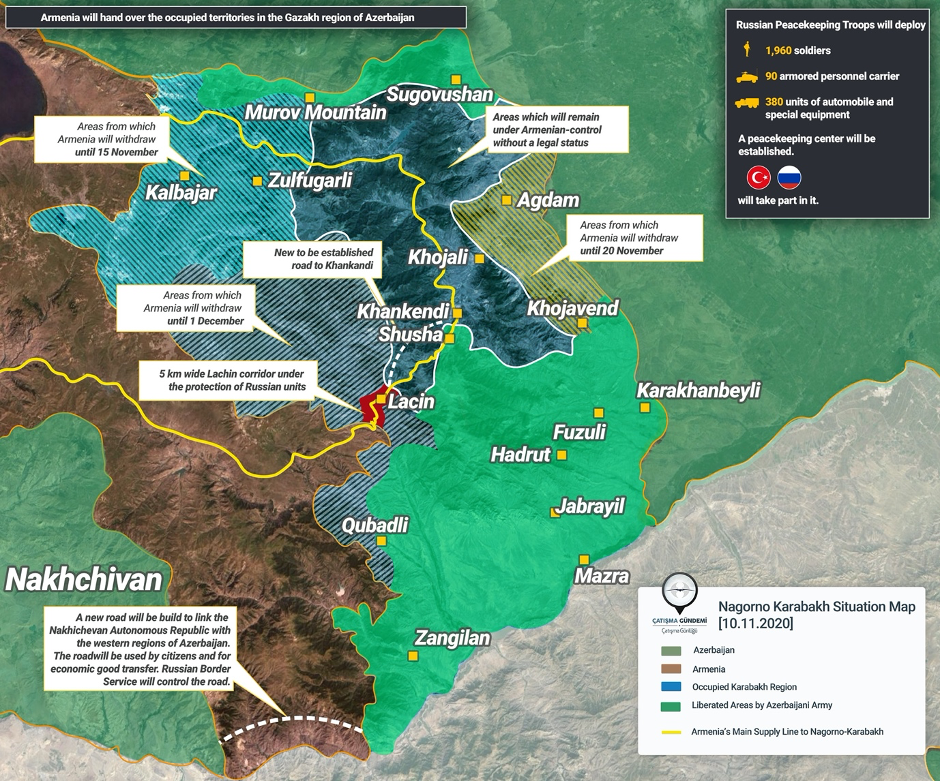

As part of the ceasefire agreement, the warring parties will retain control over the territories that they currently possess. However, by 1 December, Armenia is obliged to return to Azerbaijan the districts outside of Nagorno-Karabakh that it has controlled since 1994, as well as two small Azeri exclaves in the north-eastern region of Tavush. Armenia will retain control of the Lachin corridor, the single highway that connects Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia, which, along with the border, will be overseen by a contingent of 2,000 Russian peacekeepers. Armenia will also permit Azerbaijan direct road access through the southern Syunik region to its autonomous exclave of Nakhchivan, oversight of which will be provided by Russia’s Federal Security Service.

Figure 2 – Source: Çatışma Gündemi

ANALYSIS

In effect, the ceasefire agreement is a Russian-led implementation of five of the six provisions contained in the Madrid Principles, which have provided the basis for peace negotiations since 2007. These include the:

- return of the Armenian-occupied districts outside of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan;

- interim autonomous status of Nagorno-Karabakh;

- maintenance of the corridor linking Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh via the Lachin mountain pass;

- right of internally-displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees to return to their former homes;

- deployment of a peacekeeping force.

The only principle that has not been fulfilled is a final settlement on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh itself, approved by a popular vote.

However, the implementation of the principles that are being fulfilled has effectively been accomplished through force. In this sense, the ceasefire agreement is a major defeat for the Armenian government, which was forced to surrender many of its territorial gains from the 1992-1994 war and tolerate a “refreezing” of the conflict entirely to its disadvantage. The agreement had immediate consequences for the government of Prime Minister Pashinyan, with protesters forcibly entering parliament in Yerevan and hospitalising its speaker. The potential for violent instability was illustrated again on 14 November, when the National Security Service said that it had foiled a suspected assassination attempt on Pashinyan as part of a coup plot.

Yet the agreement has negative aspects for Azerbaijani President Aliyev’s administration, despite the substantial short-term wins. Although Azerbaijan has succeeded in winning back strategically and symbolically important territory, casualties were unsustainably high and, moreover, it is at the cost of the presence of Russian troops within its borders. The Aliyev administration has good relations with Russia, while many of its elites, including Aliyev himself, studied there and speak the language at a native level. However, Azerbaijan has successfully avoided Russian military deployments since January 1990, when the Soviet Army intervened to quell an uprising by the Popular Front independence movement, killing between 150-300 people.

The degree to which the Aliyev administration has conceded is reflected by the fact that the ceasefire agreement has not even been approved by parliament, which typically acts as a rubberstamp for the authoritarian president. Meanwhile, the Aliyev administration has not even been the most hawkish political force with respect to Nagorno-Karabakh. The Azerbaijani offensive was foreshadowed by significant pro-war protests in July, which were chiefly organised by pro-Turkic opposition groups that are critical of the compromise. An indicator of likely civil unrest would be if Baku fails to enable the return of the tens of thousands of Azeri IDPs – who are a social burden – to the districts around Nagorno-Karabakh.

The key winners of the ceasefire agreement are Russia and, to a lesser extent, Turkey. Although Russia and Turkey are rival powers in the Caucasus, Middle East and North Africa, they are not adversaries, largely coexisting despite having conflicting interests and supporting different actors. In this sense, the renewed fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh has not been a proxy war, but a conflict of domestic origin in which external powers have maximised their regional objectives.

Russia secured the greatest gains because it mediated between both sides to assume military oversight of a key conflict zone, thereby increasing its influence over the peace process. Although Moscow was unable to prevent the escalation of hostilities, this was because it was virtually unavoidable given the status of peace negotiations and Azerbaijani defence spending.

Russia has also assumed administrative control over two transit routes; namely, that between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, as well as Nakhichevan and Armenia. The absence of the USA and EU in negotiating the agreement has reinforced their redundancy in the peace process and deprived Armenia of balancing influences. Moscow’s gains were secured with the investment of relatively few resources.

Meanwhile, the Putin administration will also benefit from political instability in Armenia, which is likely to result in the ouster of Nikol Pashinyan, who came to power as a result of the 2018 colour revolution. Pashinyan, despite having maintained civil relations with Russia, is regarded with suspicion on account of his reformist democratising (and, therefore, pro-Western) agenda. Moscow’s interests would thus likely be served by political instability in Armenia, especially in light of major unrest in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan.

By playing a longer, more ambivalent game, Moscow was able to maintain its balance of power in the Caucasus. Nonetheless, it needed to manage competing interests in a region in which Russia has historically been hegemonic. Indeed, Turkey emerged as a secondary actor in upholding the new agreement. In particular, Turkish troops will run a ceasefire monitoring centre outside of Nagorno-Karabakh – although Ankara does not appear to have succeeded in having its own peacekeepers deployed.

Another win for Ankara is the perception internationally that the warfare model that it has pioneered was key in enabling Azerbaijan’s military victory. The use of cheap drones, military advisors and proxy militant groups made a significant difference in eastern Turkey, Syria and Iraq – and arguably turned the tide in Libya. Likewise, in Azerbaijan, Turkey has been one of the main suppliers to the military, selling USD 113.5 million in equipment in the third quarter of 2020 alone. Turkish drones manufactured at modest cost but in line with NATO standards were particularly prevalent, with Bayraktar TB2 drones and specialised suicide drones being used during the offensive to bypass the difficult terrain and devastate Armenia’s tank, artillery and truck capabilities. This battlefield concept is likely to become increasingly popular while no effective anti-drone abilities exist.

Besides directly profiting its defence export sector, key stakeholders in which are members of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s family or inner circle, this success creates a perception of strength domestically at a time of economic crisis. Modest trade gains are also possible, since the highway connecting Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan will provide direct land access to Turkey for the first time.

The agreement also impacts Iran, which has remained circumspect throughout the conflict. Its main interest has been in de-escalation of the conflict, especially given that there have been instances of stray rockets landing in its East Azerbaijan Province. More generally, Tehran is seeking to avoid further sources of security risks and unrest. Although the ceasefire agreement has reduced the risk of collateral damage to Iran, uncertainty as to its consequences remain. For example, if Sunni jihadists are in the area but are no longer engaged in hostilities, Tehran will be sensitive to potential cross-border incursions, whether or not those are realistic prospect.

OUTLOOK

The ceasefire agreement is likely to hold in the 5-year outlook. The main reason for this is that Armenia, regardless of the level of political instability, will be unable to launch a counteroffensive in Nagorno-Karabakh given that Russia, its only viable strategic ally, will be ensuring security there and would therefore be highly unlikely to sanction such an action.

The likelihood of a comprehensive settlement concerning the status of Nagorno-Karabakh remains low in the 5-year outlook despite Armenia’s loss of negotiating leverage. Indeed, Moscow has an interest in prolonging the refrozen conflict given the influence it can exert. For as long as the tentative security situation persists, economic development – such as through the exploitation of untapped deposits of natural resources – is unlikely.

Cyberattacks and information warfare between Armenia and Azerbaijan are very likely to continue. Skirmishes along the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan are possible but likely to be isolated incidents. Theoretically, there is scope for escalation: for example, during the July skirmishes, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence hinted that it could launch a missile strike at Armenia’s Metsamor nuclear power plant. Armenia, in the absence of any room for military manoeuvre in Nagorno-Karabakh, could target the Nakhichevan border. However, such gambits would be high-risk with no clear gains, especially for Azerbaijan. Direct targeting of Armenian assets within the country remains a red line for Russia, given that Armenian membership of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) obliges Moscow to protect its territory in the event of an attack.

The transfer of the districts surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan also deprives Armenia of a springboard from which it was able to target Ganja. This significantly reduces the security risks faced in the energy sector. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) and Baku-Supsa (BSP) oil pipelines, as well as the South Caucasus gas pipeline (SCP), all pass via Ganja en route to Georgia, Turkey and Europe. Severe damage to this infrastructure would not only have deprived Azerbaijan of export revenues, Turkey and Georgia of transit fees and key energy supply, but also European markets. For example, the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which completed construction in October, will receive Azerbaijani natural gas via this infrastructure.

More generally, the chances of Nagorno-Karabakh prompting or forming part of a regional war between Russia and Turkey is unlikely. Given the delicate balance of power in their regions of influence, combined with their increasingly stretched capacity, both Moscow and Ankara would be loath to commit resources to what would be a high-cost conflict.

Certain incidents may indicate increasing war risks, such as Azerbaijan’s shooting down of a Russian helicopter over Nakhichevan’s border with Armenia on 9 November. Yet Russia and Turkey – as well as their allies – have had five years of experience in dealing with such scenarios. There would be numerous steps in applying pressure before direct confrontation occurred, such as a Russian boycott of the Turkish tourism sector, the cancellation of negotiations on a natural gas agreement, or in extremis Russian material support for groups such as the Kurdish YPG/PKK.

Marcus How, Head of Research & Analysis

17 November 2020