Analysis – 2nd Round of the French presidential election (Apr 24th)

1. Reminder on the French presidential election process and of the results of the first round (Apr 10th):

The President of the French Republic is elected to a five-year term in a two-rounds election (run-off election). When no candidate secures an absolute majority of votes in the first round, a second round is held two weeks later between the two candidates who received the most votes.

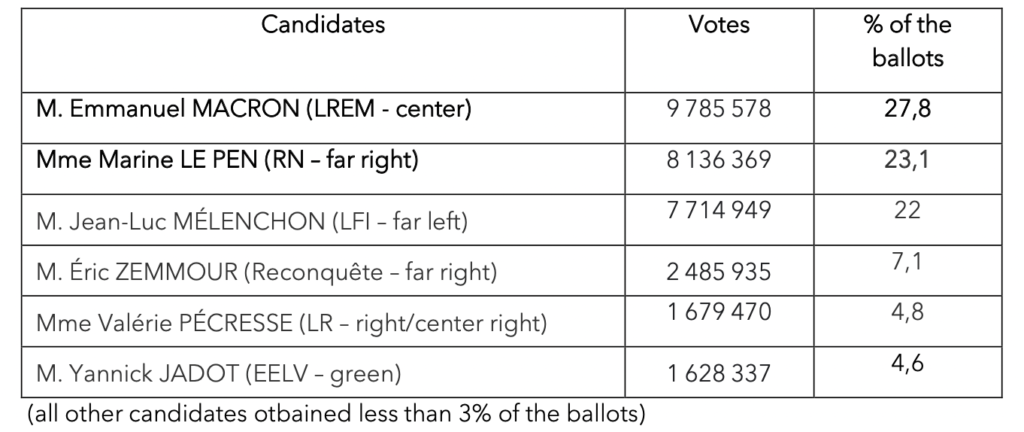

On April 10th, Emmanuel Macron and Marine le Pen qualified for the second round.

2. Main lessons of the run off

➢ The turnout was significant by international standards (71.8%), but lower than for the first round of this election (73.7%) and low in comparison to the traditional participation rate at a French presidential election run-off (usually 75% to 82%).

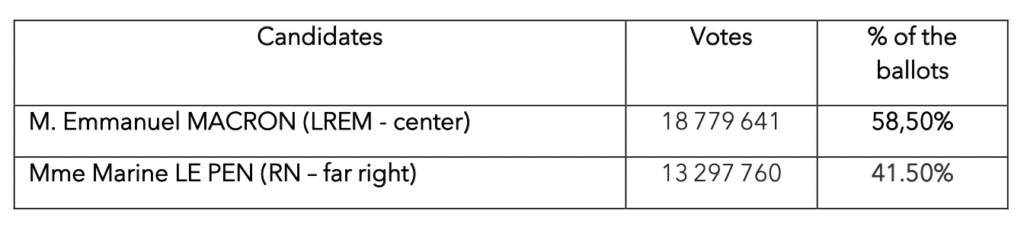

➢ Emmanuel Macron (incumbent) won a clear victory over Marine Le Pen (far-right) and will hence serve for a second 5-year term. According to the French constitution, this will be his last term. He is the first President to be re-elected with a parliamentary majority since the Fifth Republic was incepted.1

➢ This rather comfortable win does not mean Macron has unlimited freedom for the coming years:

- Even if she lost the contest, Marine Le Pen significantly increased her score from 33,9% in 2017 to 41,5% and, even more tellingly, from 10,6 million to 13,29 million votes. She also obtained more votes than her opponent in more than 18,156 of the 35 000 French municipalities. This is all the more spectacular as virtually the whole French elite expressed their support for Macron between the two rounds;

- Close to 7% of those voting cast a blank ballot, meaning they supported none of the candidates. Combined with the number of French voters who did not vote, one fourth of the electorate refrained from expressing a choice;

- More importantly, Macron owes his victory to voters who did not choose him, and with whom he is even deeply unpopular. According to pollsters, 31.75% (5.9M votes) of the 58.50% gathered by Emmanuel Macron were cast by voters who, for the first round, supported either far-leftist Jean-Luc Melenchon, Yannick Jadot (Green), Valérie Pécresse (center-right) or even Eric Zemmour (far-right). Without their reluctant support, Macron would have lost, or at least won much more narrowly;

➢ Emmanuel Macron clearly acknowledged this peculiar and fragile situation as soon as Sunday night in an acceptance speech that was uncharacteristically short and flat. The re- elected President recognized that the support of many voters who first and foremost wanted to oppose Le Pen (and not elect him) “indebted” him, and promised to “govern differently”.

How this translates into facts remains to be seen: future public policies may be impacted (between the two rounds, Macron appeared close to forego his project to push the retirement age from 62 to 65) and/or institutions may be reformed to be more “inclusive” (in particular with the introduction of referendum on popular initiative, or proportional votes in the general election process).

➢ More broadly, the French presidential election did not assuage a long-lasting crisis of legitimacy for elected politicians who are often perceived as unaware of the real problems of the “real country” (and this is particularly true of Macron) – quite the contrary.- a large chunk of the electorate voted in the first round for protest-parties/candidates, the combined vote share of which reached an unprecedented level of more than 50%. For the run-off, 60% of the electorate either did not vote, or cast a blank ballot, or supported Le Pen – a record high in a French presidential election;

- the social and geographical divide continues to widen. In Paris, Macron reaches an impressive 85% : one of the finalist candidates is almost non-existent in the capital, proof of a deep divide between decision-making circles and the rest of the French population. The place where policy is made is deeply disconnected from the rest of the country.2 More broadly, Macron won in virtually all large cities, whereas Le Pen ranked first in the vast majority of the more rural territories;

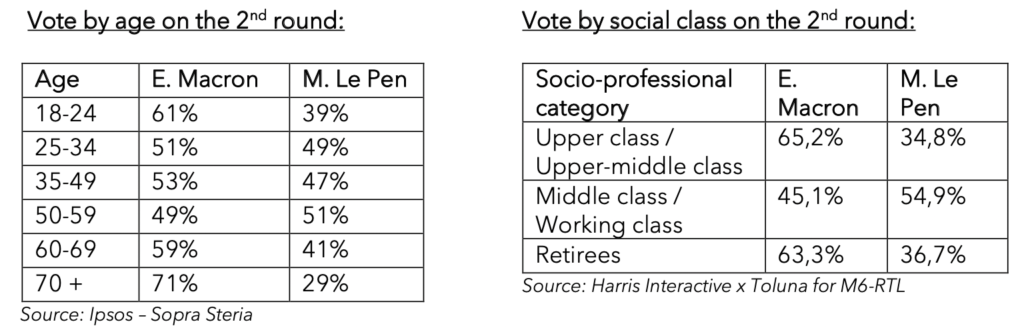

- furthermore, new divides are appearing in light of the results. Historically, even if the elderly and more affluent electorates leaned towards the classical right, while the “working class” and younger voters were more likely to support the left, both traditional parties, Les Républicains (right-wing) and the Socialist party, were able to unite behind them different kinds of people. The new landscape is much more clearly split according to age and income:

- two-thirds of voters aged 65 and + voted for Macron for the second round (and even 71% of the 70 and +), while voters aged 25-34 were almost evenly split. The 50 to 59 years old cohort even voted for Le Pen by a narrow majority (51-49%). Retirees back Macron, ageing workers back Le Pen, younger workers are divided – with many of them seduced either by the anti-capitalist spirit or by the nationalist dimension of the far-right;

- almost two-thirds of upper and upper-middle class voters cast their ballot for Macron, whereas a clear majority of the middle and working classes voted for Le Pen.

➢ In such a context, it is questionable whether Macron has a clear mandate to continue his reforms, or start new ones. Many observers anticipate street protests, maybe even Yellow- Jackets-like riots, should the President come up with policy proposals deemed to be “anti- social” or “despising of the people”. Even if such forecasts were mostly disproved in the past, the risk of unrest may well reduce his capacity to work on both a pension reform, and an improvement of the currently unsustainable situation of the public finances. Both these reforms are overdue and inevitable, but widely rejected because they build on the famous “TINA argument” that many people can’t take anymore.

As several pundints stress out, Macron’s ability to act has been impaired by some sort of “intellectual autarcy” : he and his team too often presented a piece of public policy as necessary because it was “rational” or “logical” or “the only sensible thing to do”, which is argumentation that is rejected by a large part of the electorate for precisely this reason.

➢ Were Macron to hit the wall once or twice in the coming months or years when trying to implement an important reform (and he will doubtless try to keep being a reformer), a much broader problem could arise in the form of a “crise de régime” (institutional crisis). French institutions are in theory supposed to work whatever the political situation is, but they were practically made for a political landscape constituted of two main forces (right and left) alternating according to general elections in a context of civil rest. They might be severely tested by a situation in which the ruling party fails, with the only alternatives being extremists parties unfit (and, in a way, unwilling) to govern, while part of the electorate is tempted by political violence. The probability of such an unpalatable situation will of course greatly depend on the outcome of the parliamentary elections in June;

➢ The Prime Minister should resign this week. A new government will quickly be formed and stay in office for the next two months. Former Socialist Elisabeth Borne (currently Minister for Labour) is, at this stage, regarded as the most likely to be appointed Prime Minister within the coming days. Another government (possibly with another PM) will be appointed after parliamentary elections in June.

3. The coming general election

As mentioned in our previous memo, the presidential election was only the first episode of a longer story: general elections will be held on June 12th and 19th (two rounds), determining the Parliamentary majority with which the elected President will govern the country. Party campaigns to mobilise voters began virtually immediately after the result of the presidential elections.

Even if French institutions allow for “cohabitation” (a President and a Parliament with different political programmes), such a combination is much less likely since recent institutional reforms (2000). Additionally, it is improbable that voters will change their minds within two months. As a result, each elected president was given a strong majority by the population. What about 2022?

➢ For the incumbent majority (Macron’s LREM party and allies), two main problems appear: a problem of positioning and a problem of organization and alliances.

- Emmanuel Macron adopted a right-wing agenda during the first-round of the presidential campaign, insisting on pension reform but also building on topics such as sovereignty and work in order to secure the votes of right-leaning voters. But he had to shift his position and promote left-wing proposals before the run-off to win votes on the left, and hence defeat Marine Le Pen. However, because of the two-round majority ballot, which is known to overrepresent the main parties capable of forging alliances, it is likely that the main opponent of “La République en Marche” during the general election will be the left-wing. This is strengthend by the fact that the presidential party has also lost part of its left-wing electorate this year, which has been more than replaced by the contribution of right-wing voters (45% of Sarkozy’s electorate in the first round of 2012 voted for Emmanuel Macron in the first round this year). How the President deals with these contradictions remains to be seen.

- Another problem is the composition of the majority. Indeed, no less than seven political parties are already negotiating inside the majority the dispatch of “winable” constitutencies. Despite Macron’s proposal to unite everybody under one flag, the smaller parties composing his likely majority are reluctant to join as it would mean the end of their public funding. In addition, bringing together candidates from social democracy to Gaullism including quasi-Greens has its limits in terms of feasibility. Finally, such a catch- all logic presents risks for the future: the majority might well end up quite unstable because of “slingers”, and a union of all the “centrist” sensitivities would leave the field open for all sorts of radical alternatives.

➢ Already divided in the presidential election, the left seems doomed to tear itself apart once again in the general election. One party seems to have all the cards in hands: “La France Insoumise” (LFI), headed by Jean-Luc Mélenchon (far-left). Following his strong performance in the first round of the presidential election (20%, ranking third), the collapse of the Socialists (1.75%) and the disappointing results of the communist (2.3%) and ecologist (4.6%) candidates, he believes that a left-wing majority in the National Assembly is within reach (even if LFI has only 17 incumbent MPs ). But, first, some of the parties likely to constitute this majority will feel uncomfortable with the quasi-revolutionary program of LFI and, second, Melenchon’s offer to dispatch the winable constituencies according to the results of each party at the first round of the presidential election is far from attractive to them given their scores.

The path to a comprehensive agreement on the left from the first round therefore seems very narrow.

➢ For the right, but also for the far-right, the issues are also numerous:

- In the 2017 parliamentary elections, because of the voting process, the National Front (FN) obtained only seven MPs (1.2% of the seats) – despite its presence in the second round of the presidential election and 13.2% of the votes in the first round of the parliamentary election. Marine Le Pen delivered a quite tough speech after the announcement of the results on Sunday night, but her party still lacks allies and it seems unlikely that there will be an alliance with Eric Zemmour’s party “Reconquête!” after his attacks during the campaign. Moreover, his candidacy was very “personal” and the lack of well-known figures in his party is going to be a weakness during the parliamentary election instead of an advantage. It would also be an unstable alliance as the National Rally tried during the past months to appear as the “working class” party, whereas Zemmour appeals more to intellectuals and the upper-class worried by cultural changes linked to immigration;

- As for the “classical” right-wing, survival is at stake. After its historic defeat (less than 5% of the votes), with a lack of leadership and divisions between the line to adopt. The debate is open between those defending an alliance with the majority in order to govern, and those willing to keep up the fight with 2027 in the line of sight and the insurance that Macron will not be allowed to run again.

In conclusion, the likelihood that Macron will secure a majority is high even if the loss of the « freshness » that characterized his campaign in 2017 will not allow for the landslide he obtained then.

Forcast

Even if less clearly than 5 years ago, Emmanuel Macron should be able to secure a majority after the parliamentary elections in June, either (most probably) on his own, or (much less probably) in an alliance with part of the “classical” right (Les Républicains). Still, the Assemblée Nationale will remain poorly representative of the French people from a sociological point of view.

References

1 Except François Mitterrand in 1988 and Jacques Chirac in 2002 but, in both cases, the incumbent had had to deal with several years of “internal opposition” after losing the general election during their term, which was not the case of Macron who enjoyed a comfortable Parliamentarian majority during his whole first term.

2 The same phenomenon was observed in the United States, where Trump only garnered 8% in Washington DC in 2020 e.g., but the meaning of such a differential vote is far greater in Paris where civil servants weigh much less (in %) than in DC.