Analysis – 2022 French General Election – June 19th 2022

1. Reminder on the French general election process and the results of the first round (June 12th)

Since the inception of the Fifth Republic (1958), all legislative elections have been held under a two-round system with single-member constituencies, except for the 1986 elections. Each voter has one vote: in the first round, a candidate must get an absolute majority of the votes cast, representing at least 25% of the registered voters (not just the votes cast) to be elected. If no candidate is elected, a second round of voting is organised one week afterwards.

The constitutional reform of 2005 brought about two significant changes: the reduction of the term of office of the President of the Republic from 7 to 5 years (thus coinciding with the tenure of the deputies) and the so-called “inversion of the electoral calendar”, meaning that legislative elections are now held shortly after presidential elections. This has resulted in two facts:

- Before Emmanuel Macron (and since 2002), no president had been re-elected for a second term;

- Before Emmanuel Macron (and since 2002), all elected presidents have won an absolute majority in the legislative elections following their election (increasing their score in the process).

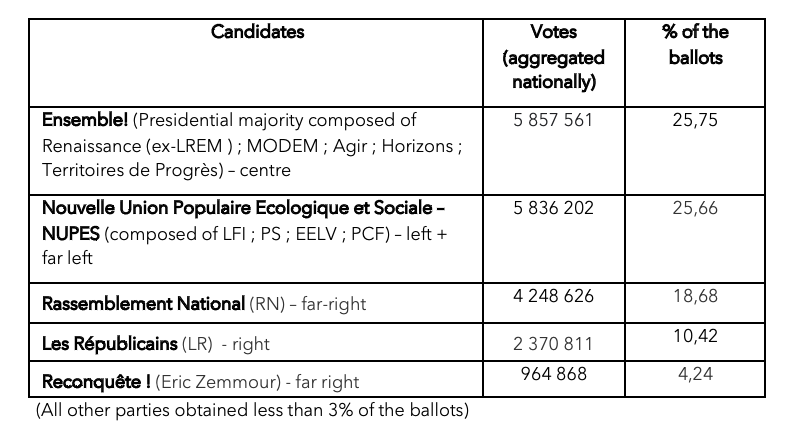

As a reminder, the results of the first round of the election held on June 11th were the following :

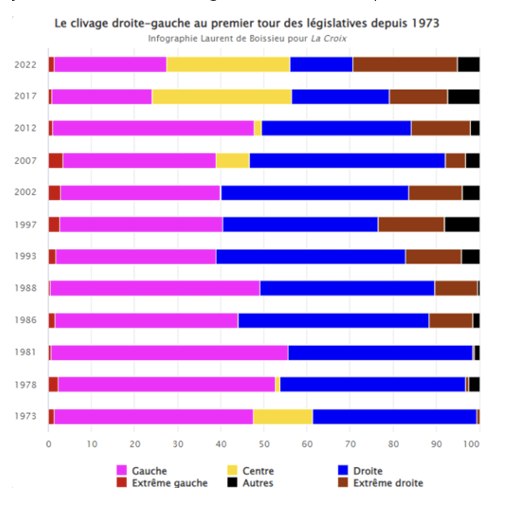

In terms of % of votes cast, these results confirmed the tripartition of French politics that began in 2017 (after half a century of a more classical right vs. left landscape):

2. Main lessons of the runoff (June 19th)

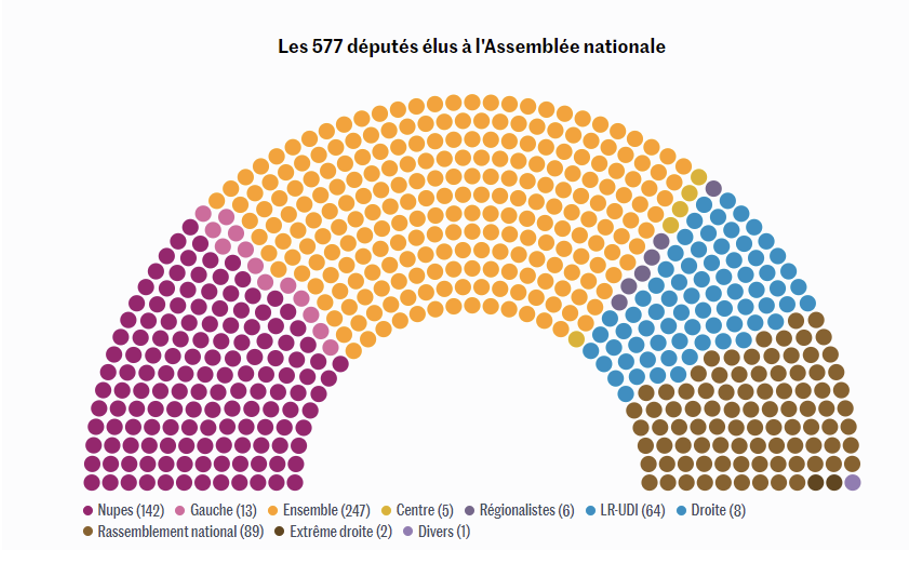

- Absolute majority = 289 MPs

- As a reminder, the turnout during the presidential election was significant (71.8%) but lower than for the first round of this election (73.7%) and low in comparison to the traditional participation rate at a French presidential election run-off (usually 75% to 82%).

- These general elections, however, were again victims of the growing disinterest of the French population in most elections, with a turnout rate of 47,51% during the first round and 46,23% during the second one. Reminder in 2017 : 48,70% (1st round) and 42,64% (2nd round)

- According to a survey (Ipsos-Sopra Steria) conducted after the first round, 49% of respondents found the campaign “non-existent”, 36% “disappointing”, and only 16% “interesting”.

- Abstention was particularly high among young people, with 69% of 18-24-year-olds and 71% of 25-24-year-olds not voting.

- Year after year, a growing disinterest of the population in the legislative elections and the Parliament is to be observed. Only 44% of French people have confidence in the Assemblée nationale (Ifop – Vae Solis 2022).

- Several facts can explain this disinterest:

- In a context of fragmentation of political representation, the “majority vote” (two-round system with single-member constituencies), if bringing theoretical stability, tends to disappoint voters who do not see the point of voting if their voice is not heard. For example, in 2017, the RN received more votes at the national level than the PS, yet only 8 RN MPs were elected against 30 PS MPs;

- In this respect, the multiplication of “small parties” and federations this year has made the political offer incomprehensible and unreadable for the uninitiated;

- In the same way, most of the leading politicians were not candidates (Jean-Luc Mélenchon (leader of LFI), Edouard Philippe (former PM and leader of Horizons!) etc.);

- The abolition of the accumulation of mandates (mayor + MP as an example) has led to a certain apparent disconnection between elected representatives and their constituents, resulting in a schizophrenic judgement: MPs are criticised for not being present enough locally and at the same time for deserting the hemicycle of the Assemblée nationale;

- Finally, after two years of covid and the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the political debate has been (partly) sedated.

- As the vote and the outcome of those elections are increasingly delegitimised, and as campaigns (or the lack of them, to be more precise) have not allowed for the confrontation of ideas and the purging of tensions in the country, the risk of new social phenomena such as the yellow jackets movement of 2019-2020 has increased.

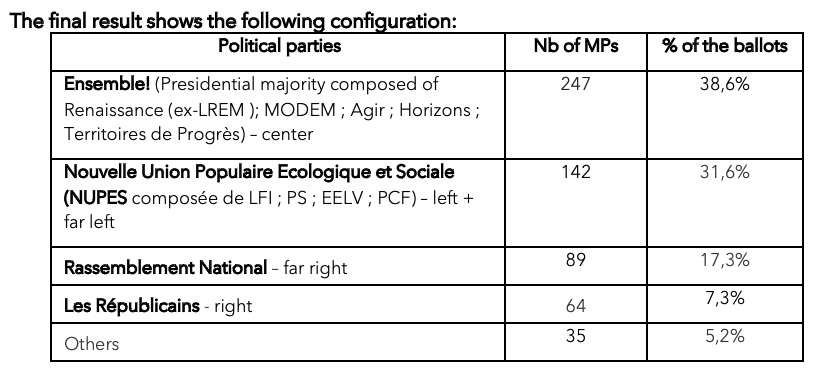

- The final result calls for various observations on the conduct of these elections:

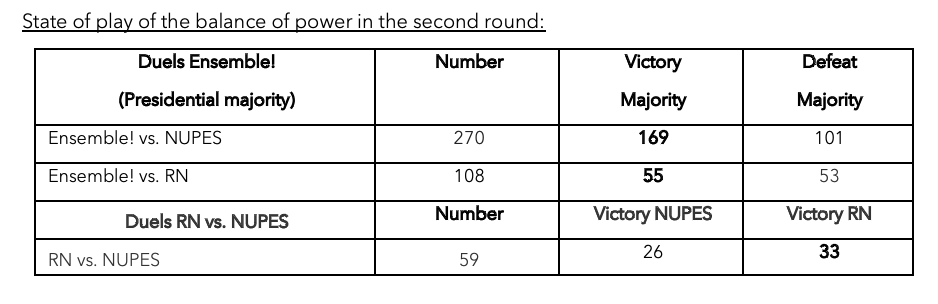

- The three political parties that came out on top in the first round of the presidential election once again dominate the polls, but with an altered balance of power. Ensemble!, the coalition of the presidential majority, suffered a significant defeat. There was no momentum, contrarily to what Emmanuel Macron was betting on;

- The re-election of Emmanuel Macron for a second five-year term (a situation unseen since 2002) has led to a second unseen situation, the absence of a majority for an out-of-cabinet president. Several explanations can be given:

> The historic feat of re-election has brought a drop in the usual enthusiasm accompanying a presidential victory due to a lack of “novelty”;

> Emmanuel Macron was mainly re-elected thanks to the rejection of others and, in particular, the extremes (Le Pen and Mélenchon etc.) more than he was praised for his first term. As a result, the voters’ choice and will to entrust him with a solid majority to govern has been diminished;

> Emmanuel Macron failed in proposing a clear and ambitious project, leading, once again, to hesitation from voters.

The presidential party and its allies hence suffered a significant and historic failure to achieve an absolute majority in the Assemblée nationale. In addition, several key figures in the majority were defeated: Richard Ferrand (président of the Assemblée nationale), Christophe Castaner (former president of LREM, the “parti du Président”, and former Minister of Interior), several recently appointed ministers (Amélie de Montchalin, Brigitte Bourguignon, Justine Bénin).

- The Rassemblement National has taken root and gained momentum, losing a few points compared to the result of the presidential election but making real progress compared to the 2017 legislative elections (+200% ballots).

- Never before has this party obtained such a score in a legislative election;

- In 2017, the Rassemblement National was present in the second round in only 120 constituencies, compared to more than 200 this year, moving into regions where it was not present until then;

- Moreover, for the first time in its history (except for the 86-88 parenthesis, when a dose of proportional representation was introduced into the electoral system), it can form one of the most potent parliamentary parties in the Assemblée nationale, with 89 elected MPs (multiplying by eleven the number of MPs elected in 2017);

- However, underneath its apparent solidity, the party risks being prey to an inevitable destabilisation during the five years when the question of the candidate’s designation for the next presidential election in 2027 approaches. Indeed, after three defeats in the presidential election, it will be difficult for Marine Le Pen to convince voters again of her ability to win.

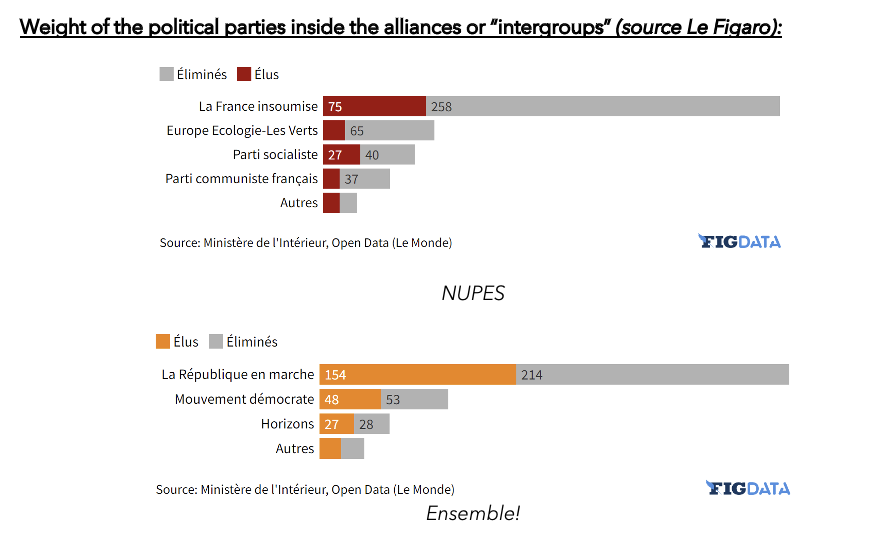

- Jean-Luc Mélenchon pulled off an impressive tactical coup by managing to federate the left around him (more than around a joint programme, by the way) while taking advantage of the absence of a campaign from the presidential camp (which tried, mistakenly, to reproduce the tactics used during the first round of the presidential elections) and the sluggishness of Marine Le Pen and the RN.

- The left is coalescing around its most radical fringe for the first time in its history, thus shifting the ideological centre of gravity of the (parliamentary) left. The line adopted is heteroclite, mixing social redistribution, intersectional struggles, wokism and ecological planning, and is far removed from the concerns of the middle and working classes;

- Nevertheless, this line seems to echo among young people: in the first round, 42% of 18-24-year-olds voted for the NUPES and 36% of 25-34-year-olds;

- However, the NUPES alliance has already started to crumble since Sunday evening through the voice of the National Secretary of the French Communist Party, Fabien Roussel. The latter considers that the current discourse is not likely to speak to rural France, as shown by the vote for the National Rally.

- If Eric Zemmour had partly succeeded in infusing his theses into the public debate (60% of the French believe in the risk of a “great replacement”), he would not have succeeded in transforming this into an electoral victory with no MPs elected.

- Unlike the Socialist Party, which has become a satellite of the NUPES, Les Républicains are surviving. Still, they are victims of what could be called a “baronnisation” (i.e. the local “heads” of the party are gaining power in comparison to the national). They are certainly saving their strongholds but are disappearing from a large part of the electoral map with scores around 5 to 10% in many constituencies.

- However, it is essential to underline an important paradox. While the historical right-wing party is weaker than ever in the Assemblée nationale, the partition of representation and the absence of an absolute solid majority make it decisive in case of difficulties for the majority. It is in theory an indispensable ally for Macron;

- Actually, this might be a real challenge considering the remaining Les Républicains MPs are the defendants of a virulent “anti-Macron” line and refused any alliance with the presidential majority.

- The “Republican Front” (an expression describing the long-lasting idea that all parties should unite in elections to barrage Rassemblement National), has been shattered. With 89 député (15% of their number), Marine Le Pen’s party has now settled in the institutional landscape (whereas it was once only present in the political landscape).

- Sociologically, the right-wing electorate has “slipped” towards the presidential majority, as shown by the vote in Paris where the West (traditionally right-wing) went to Ensemble! while the East (historically left-wing) went to the NUPES. Moreover, the strong personalities of the presidential majority are from the right-wing (Darmanin – Minister of Interior, Le Maire – Minister of Economy, Philippe Former PM and head of Horizons! or Lecornu Minister of Defence).

- Generally speaking, with an abstention + blank vote at 56.31% and an “extreme bloc” (LFI + RN) with 164 deputies, i.e. a little less than a third of the National Assembly (which is historical), we observe once again a symptom of the democratic crisis that affects France.

3. Consequences on the Assemblée nationale

The result of the legislative elections shows an extremely fragmented assembly, as was the case under the Fourth Republic when deputies were elected by proportional representation.

This model is characterised by instability of Parliament, which is subject to bargaining and alliances of circumstances (historically often translating into government instability). However, unlike a chamber elected by proportional representation with a so-called ‘list’ system (where voters vote for a political party directly and not for a candidate), having a fragmented chamber with MPs elected by single-member constituencies is likely to have a consequence on their individualism, favouring their local roots in a context where they will not be able to benefit from a third ‘Macron’ wave. This will only increase instability.

- For the presidential bloc, its relative majority is a source of multiple risks. Negotiations will be permanent between the different groups composing it, and an internal fragmentation may very quickly appear, with deputies understanding that they ‘weigh’ more in a small but decisive satellite group (such as Horizons) rather than in the majority group. As an example, during the previous legislature, while the LREM majority group had 314 MPs at the end of the 2017 election, this number was reduced to 270 in 2022 due to defections for various reasons. Again, this phenomenon is likely to increase during the quinquennium, when the deadline for the end of Macron’s second (and last) term approaches.

- As such, the seemingly large blocs formed by ‘intergroups’ (i.e., federations of parliamentary parties) such as NUPES and Ensemble! may not hold together for long. Indeed, ‘intergroups’ are not recognised from a regulatory or constitutional point of view, so MPs must attach themselves to legally unique political parties. This is of paramount importance since the number of MPs determines (in part) the amount of public subsidies given to the different political parties.

- By becoming the second-largest parliamentary party in the National Assembly, and ipso facto the largest opposition parliamentary party, LFI (far-left and main component of NUPES) can benefit from essential advantages:

- Vice-presidencies of the Assemblée nationale (crucial for the organisation of votes, conducting the debates, and conducting the work of the Assemblée nationale in general);

- The “Questure” (critical for the logistical functioning of the Assemblée nationale and the knowledge of all the internal files related to the administration and the MPs);

- The chairmanship of the powerful Finance Committee, responsible for examining the budget, has a unique role in the admissibility of amendments and certain investigative powers, particularly in tax-related questions.

- The granting of these various advantages is nevertheless subject to a set of votes whose modalities are more a matter of custom than the rules of the National Assembly. There is therefore a strong possibility that alliances of circumstance will emerge from the beginning of the legislature to ‘prevent’ the far-left party from accessing these responsibilities (at least the most sensitive ones). Moreover, if the NUPES were to split up under different banners, the Rassemblement National would become the second-largest opposition group.

- Keen on “coups” (commissions of enquiry, circumstantial alliances, media stunts, etc.), LFI can make the Assemblée nationale a centre of French political life, in contrast to the past years when the place of Parliament in institutional life was reduced to a minimum.

- In this context, the Senate, which is institutionally relatively weak but historically very stable, can become a pivotal chamber between the Government and the National Assembly. However, it should be noted that half of the Senate will be renewed in September 2023. Although it remains traditionally right-wing because of an indirect election favouring local roots, the next renewal, generally scheduled for September 2023, could be affected by the political climate. In this respect, several large cities in France went under the ecologist banner in the last municipal elections, creating a new contingent of local elected representatives who are more inclined to the left, which could influence the vote.

4. Conclusion

- While the presidential election is usually full of surprises and the legislative elections are not very surprising, 2022 has proved the exact opposite. The presidential election was announced (in particular by the pollsters who tried, on this occasion, to restore their image). In contrast, the legislative elections brought us to a pretty unprecedented situation in the Fifth Republic.

- The first institutional revolution of the Fifth Republic took place in 1986 with the first “cohabitation”, the second took place in 1988 with the first relative majority for a government, and the third took place this Sunday, June 19th, with the addition to a relative majority of several radical oppositions (and no longer only one).

- The solidity of the French regime is called into question for the first time in its history since 1958. By not obtaining an absolute majority, the government can fall whenever a motion of censure is adopted. Therefore, the period ahead will confront unprecedented difficulties in a worrying socio-economic and international context. It should also be noted that the government’s weapons for governing despite everything are strongly hindered in a context of relative majority. Thus, in addition to the risk of social blockage resulting from the absence of debate during the campaign (cf. above), there is a risk of institutional blockage that could paralyse the country.

- The equation seems almost intractable for the majority, which does not find itself in a minority position facing one opposition, but several oppositions contrary to each other. As a result, each constructive step toward one of the oppositions will lead to internal negotiations within the majority, of course with François Bayrou (head of Modem) and Edouard Philippe (head of Renaissance) and within the presidential party Ensemble! itself, as it has been heteroneous and composite since its inception. The negotiations will be made even more difficult by the disappearance of heavyweights of the majority who were defeated on June 19th, Richard Ferrand and Christophe Castaner in particular.

- However, NUPES, RN and LR should very rarely vote unanimously. Hence the balancing act will require extreme political and parliamentary management skills.

- In this context,we believe that the cabinet may have to be changed quite radically and relatively quickly to:

- Secure a majority by proposing a government agreement to LR, for example;

- Put a more experienced political staff in front of a chamber that is particularly difficult to control;

- Replace the three defeated ministers appointed following Emmanuel Macron’s victory who in any case already have to resign;

- A first test for the majority should take place quickly as on July 5th, Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne will have to deliver her general policy statement, followed by a vote of confidence from the National Assembly. In case of defeat, she will have to resign;

One may think that Borne will resign even before that and be replaced by someone more likely to win a vote of confidence.

Ironically, in 2017 Emmanuel Macron praised the advantages of proportional representation at Parliament and even made it a campaign promise. He is now getting a similar result… without having to make any institutional reform. This brings him to a difficult situation where he can:

- Enter the arena to carry out his reforms at all costs with coalitions of circumstances or by using the referendum, aware that this is his last mandate. This, at the risk of damaging his image (in case of failure) and the office (the President of the Republic is supposed to remain above partisan politics);

OR

- Remain very high up and take advantage of the status conferred by the French Constitution to engage even more on international issues and “neglect” domestic issues. This seems however barely feasible as both the EU commission and the ECB will now push towards structural reforms aiming at altering the fatal curse of an ever more indebted large member-state.

Of course, in case of a lasting institutional blockage, Macron could also use his constitutional power to dissolve the Assemblée nationale and call for a snap election. But this powerful weapon can be used every 12 months – and, in any case, it wouldn’t serve him well to dissolve quickly as the results of the election could well be similar, or even worse for the presidential party.

Finally, it is worth noting that one consequence of this election is that Emmanuel Macron now finds himself weakened on the international level. In a sensitive global context, an institutional paralysis of the only remaining nuclear power in the European Union is likely to add to instability.